In the last 15 years, the education sector has shown a full blown exponential growth in terms of enrollment rates, governmental expenditures, investments, (and of course tuition fees, notably in the private education). This gaining of exponential momentum is remarkably evident in the MENA education sector more than anywhere in the world. Perhaps this is Partly due to the Arab Spring, most governments in the region have taken serious steps and announced large spends toward improving social infrastructure (education and healthcare).

However, Despite high spending on education by respective MENA governments, the quality of education in the region has remained below global standards, an issue that parents and the job market have been pointing towards. Employers in the region always preferred foreigners rather than nationals to fill vacant/new positions as the locals were always perceived as not having the requisite skills required for some jobs. Public resentment always existed; however, the onslaught of the Arab Spring forced governments in the region to realize their education system was faulty and not giving the desired results.

Education is becoming an attractive business proposition and the MENA. K-12 education market is experiencing increased levels of activity. Private equity firms are interested to associate with this sector due to factors such as long-term revenue visibility, demand being greater than supply, and negative working capital (as school/tuition fee is paid in advance by parents and generally they do not default on dues). The MENA region has had an incremental inflow of ~300,000 new pupils during 2010–15, driving demand in the education sector. With better enrolment rates, lower dropout rates, higher government spending and demand for private education, the education sector in MENA is set to grow robustly. The AlMasah Capital Limited research suggests the public and private education market in the MENA region is estimated to be worth USD96 billion in 2015; with the GCC region alone being worth ~USD61 billion of this. The private education market in MENA and GCC is estimated to be worth ~USD11.2 billion and USD5.5 billion, respectively,in 2015.

However, this opportunity is not free of concerns. The quality of education has not been good in the MENA region, resulting in relatively high unemployment rates and dissent amongst the youths. Although private establishments are now coming into prominence, course curriculum has to be updated continuously so that pupils are kept abreast with the latest developments across the world and are armed with all the tools required to improve the region’s competitiveness.

In terms of value, the largest private education markets would be Egypt (USD3.5 billion), Saudi Arabia (USD2.2 billion), the UAE (USD1.4 billion) and Kuwait (USD0.83 billion). In terms of the number of private sector enrollments, Egypt would be the largest market, with approximately 2 million pupils in private schools, followed by Saudi Arabia (580,000 students).

Government spends in education sector

On an average, the MENA region is expected to experience a recurring spend of ~USD29 billion on education over the next couple of years, with Saudi Arabia being the leader as it continues to invest more money in building committed infrastructure in KSA. The government spends on education in a substantial manner in MENA, with contribution from the private sector being miniscule. Such public expenditure helps in attracting pupils as well as teachers intending to be employed. Data from the World Bank suggests that public expenditure on education in the MENA stands at 19% compared to the world average of 14.5%, North America average of 14.1% and the OECD average of 11.6%. Among MENA nations, public spending on education receives high priority, particularly in Oman, Morocco, the UAE, Tunisia and Saudi Arabia.

Increase in demand for private educational setups

Despite relatively high public spending on education, MENA as a region lags behind in providing quality primary and secondary education to children. This can be mainly ascribed to relatively under-qualified teachers employed in public institutions and the lack of updated educational curriculum. This has resulted in parents (national and expatriates) seeking for private education for their children. Demand for private education has been on the rise in the MENA region, thus leading to strong growth in the education sector. Private enrolment has been on an uptrend in the MENA region in the past decade; it rose to 28.7% in 2010 from 24.3% in 1999, higher than the latest world average of 10.9%. The rise reflects higher demand for private education in the MENA region. Among GCC countries, the UAE (63.9%) and Qatar (48.1%) accounted for the highest private enrolment (primary and secondary combined) in 2010. In MENA, excluding GCC, Lebanon (66.8%) accounts for the highest private enrolment during the same period.

Quality of education

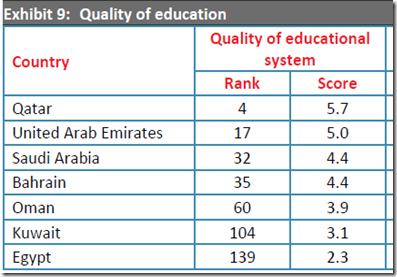

The quality of primary education in the MENA region is still below the standards in developed nations. World Economic Forum (WEF)’s Arab World Competitiveness Report reasserts the importance of quality education for improvement in Global Competitiveness Index in the MENA region. It recommends policies that would include implementing specific education and labor initiatives (internships, vocational training and continuing education) to align the supply and demand of skills; enhancing the flexibility of labor policies to adapt to changing markets; integrating women in the labor force; and fostering linkages between foreign enterprises and local suppliers, mainly through the use of economic zones. The WEF data suggests some countries, particularly Libya, Egypt, Morocco and Algeria, need to improve their quality of education at the primary level. It also appreciated the steps taken by Qatar, which currently ranks among the top five nations globally in terms of the quality of primary education.

The MENA region has 17 students for every one teacher (a pupil-teacher ratio of 17:1) compared to the world average of 24:1. However, the knowledge level and skill set among students in the MENA region is still relatively lower compared to their counterparts in the developed countries. This can be mainly ascribed to the poorer quality of teachers in the MENA region. Skilled teachers are essential in an education system as they are the ones who impart knowledge and values to the future generation. However, countries in the region face an acute shortage of teachers. Therefore, those hired to serve as teachers are often not adequately qualified for the position. This results in lower knowledge level and skill sets among students. Students in MENA score lower on Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS4) compared to the average score in developing/developed regions.

Women education

The share of females amongst total illiterates in MENA stands at 65%, a notch higher compared to the global average of 64%. GCC fares better within MENA, with an average female illiteracy rate of 54%. The startling level of female illiteracy prevailing in the non-GCC part of MENA is a concern. Among GCC countries, the highest number of adult female illiterates is found in Saudi Arabia (59%), followed by Oman (56%). Overall, in MENA, Libya leads with an astounding 80% female illiteracy rate, followed by Jordan (71%), Lebanon (70%) and Tunisia (68%).

Female illiteracy is a bane for the entire region in terms of social and economic costs. Although certain efforts have been made by individual countries to educate female masses, it is in no way sufficient. Coupled with the political turmoil in the region, the plight of women education is expected to remain grim in MENA. Among GCC countries, Saudi Arabia has allocated ~USD593mn towards women-focused educational institutions; however, it just represents ~10% of total spend towards education over 2013–16.

Final thoughts

With all these whopping expenditures in the MENA region, the quality of education in k12 schools, vocational training, and even higher education is still low, by far lower than the developed countries, and lower than some developing countries. The main problem is in the nature of these expenditures and investments. Talk to any educator, administrator, or policy maker and he’ll tell you that most of the spending goes to constructions and facilities. However, educational institutions are human institutions, where people get to become “good” citizens as and more importantly than becoming “successful” citizens. So, when governments and private education sectors through this spendings on IT infrastructures, scientific labs, and the like they ought to think of how to improve the human capacity in terms of quality teaching and quality educational leadership. Until then the education sector in the MENA region will only painfully and “snailfully” progress, still lagging behind the developed countries.

Comments

Post a Comment